Climate Story: Siri Vorvick

Stories help people connect with one another and can move us to action. Storytelling is a core component of the Environmental Justice class at the University of Minnesota, with MNIPL’s Dr. Julia Nerbonne. This spring, Jothsna Harris, founder of Change Narrative, and Whitney Terrill had the privilege of mentoring four students as they worked on their own and community climate stories. We are excited to share their words!

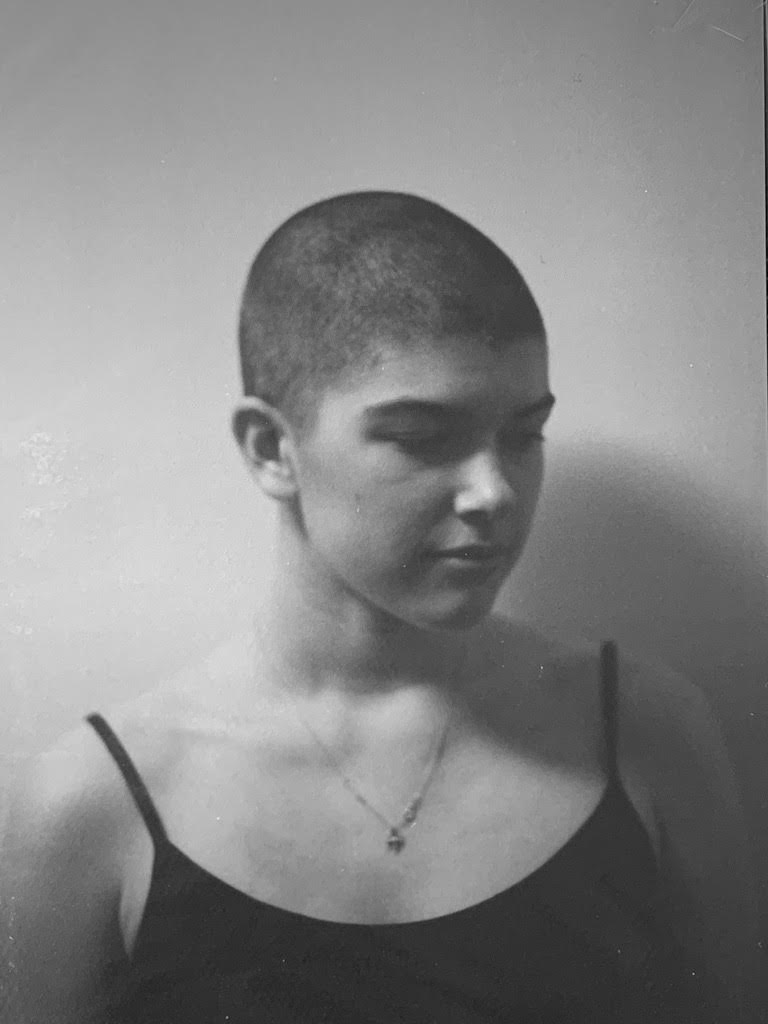

On a regular night at the end of March, me and my two best friends went through the process together of shaving my head. I was apprehensive about the transformation, but they were enthusiastic, supporting me. In the grand scheme of my life, I know the night makes up very little—but it signifies so much to me now. It represents my growth, my confidence, and how I am working to bring the parallel lines of who I am and how I want to be closer together.

Shaving my head has always felt like an unattainable dream. This is because the action itself never felt under my control. For my whole life, I have placed the decision of how I should look and what attention I deserve in others’ hands. However, I am now at a point in my life where I have learned I can draw a boundary between others’ opinions of me and the choices I make for myself and my image. I now appreciate that how I express myself is completely up to me—this agency is liberating and has brought me closer with the world around me.

However, this semester has challenged me beyond my personal self-expression, to think critically about my place in the world as well as how I interact with it. In my classes, I am learning about things far bigger and more important than myself—topics like environmental justice, Latinx immigration, and the resulting and undeniable links between climate change, forced migration, and the US policies that are destroying the lives of people seeking help. These systemic issues prompt me to put my own experience into perspective: the complications and harms of climate change and forced migration are on a much broader scale and have much greater implications than my evolving expression of self. Learning about these issues more in-depth, I hope that I can use my newfound confidence in my self-expression to translate to power in my voice, speaking out against these systemic issues and fighting for greater change in our world.

In my Latinx Immigration class, we often learn about the big picture. But an important component of the class is the personal experiences embedded within that larger narrative: the stories told by people forced to migrate to the US. These always hit me the hardest—first-person stories are such a direct way to recognize someone’s humanity, a much more impactful experience than reading numbers and statistics in the news about people with very different lives than mine. They allow me to feel the injustices that proliferate our world and so harmfully affect people’s lives.

The importance of personal narrative particularly struck me with one story of a Guatemalan family, forced to leave their farm due to the devastating impacts climate change has had on the land. Both the father, Max Ronaldo Herrera Figueroa, and mother, Lleny Suleyma Escobar de Herrera, shared their experiences of trying to get themselves and their two small daughters across the border. They were separated while trying to cross, the mother and youngest daughter almost losing each other as they climbed a piece of the border wall, and the Dad and elder daughter trapped in a smuggler’s house in the desert for weeks before being sent to Mexico. The trauma of this story was apparent in the voices of the parents, and their words betrayed the indecision about what would be best for their family. They discussed the sorrow they felt about the changing land their family had lived off of for generations, and the fears they struggled with about how to continue in the place that they loved after being unable to move to the US.

This story was related by the pair in an interview conducted in Spanish. Because of my own grasp of the language, I understood their story—and this led me to an interesting and personal realization. I understood their native tongue, which is a new experience for me as I have not had this ability in Spanish before. And with this new knowledge, I could feel the depth of their words in a new way, and empathize with them as I processed their inflections and tone of voice. The emotional charge of what they faced was clear as they described it. However, when I read the English subtitles (as I am used to), much of this human connection was reduced—the subtitles were a simplified version of their story, translated without the eloquence or personality that they were expressing in their own narratives. This now seems very important to me. It has put the issue of personal agency in a whole new light, because I have now realized the depth to which the ability and access to opportunities to express and speak for oneself is a privilege, and how many people’s stories are misinterpreted because their voices are not respected. If someone’s voice is changed or taken away from them, it completely changes how others perceive the—something I see happening in this country’s debate about immigration, and to other people on the frontlines of the climate crisis and other injustices in our country. If the lives and perspectives of immigrants are constantly being simplified and lost in translation in this way, it is easier to disregard their experiences and dehumanize their perspectives.

I am not claiming that this was the intent of the video about the family from Guatemala—actually, I think the opposite is usually true. In an attempt to tell the stories of others, especially through translation, it is all too easy to reduce the impact of their words. This is why the voices of the affected must be paid extreme attention to and treated with a lot of care. And this is why I cannot disregard the privilege I have in being able to choose my own self-expression and perception, when many people have it decided for them in society, based on their nationality, race, level of education, gender, physical ability, access to power, or other factors that are often linked with climate injustice or discrimination.

This semester has prompted a personal process for me, and shaving my head was part of that process to recognize a greater awareness of self and of the world around me, and the privilege that I have in it. I have been inspired to deeply respect the power of self-expression and the power of our stories, especially for people whose voices are often minimized in our society. I cannot just use my voice for my own self-expression—I have to be aware of its power and use it to amplify the voices of others that are in more danger of being misinterpreted.